For my 40th Birthday (dear reader, I won’t even tell you how long ago that was). My husband gifted me a first edition of The Great Gatsby.

I died.

Then I revived myself because, Hello! My husband is amazing and he got me a first edition, first printing of The Great Gatsby. There’s even mistakes that Fitzgerald corrected for the next printing. I feel a tiny spark of joy knowing this, because much of the brilliance of The Great Gatsby is about craft.

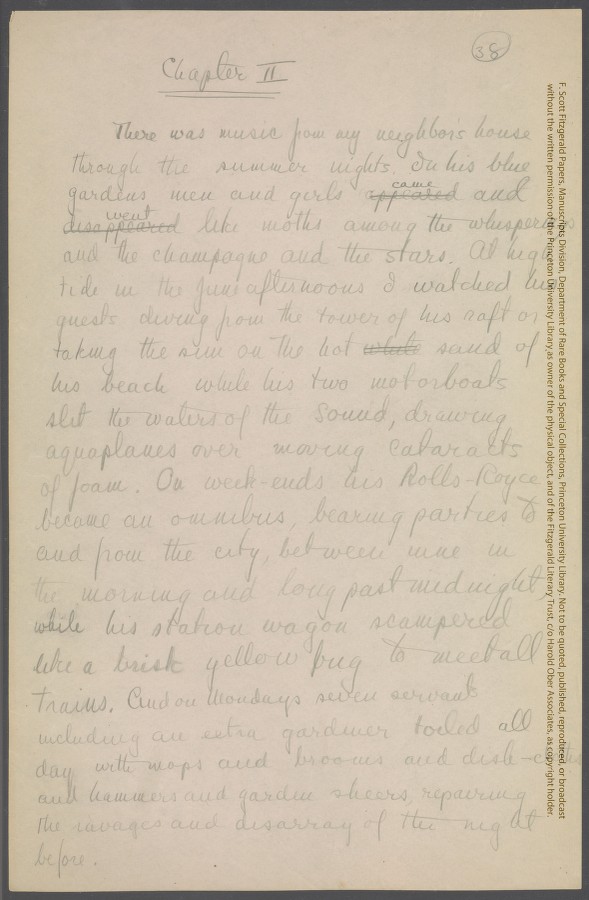

For me, The Great Gatsby is one of the most finely crafted novels of the American 20th Century. It has its problems, but it also has lyrical sentences like this one in Chapter 3: “In his blue gardens men and girls came and went like moths among the whisperings and the champagne and the stars.”

Here are those words in the earliest surviving draft of Gatsby (from 1924), in Fitzgerald’s handwriting, housed at the Princeton University Library

Virtually flipping through the manuscript is like opening a tiny door into the mind of the writer at work– the words that he changed and changed again, notes to himself, notes on the galley, passages he saved.

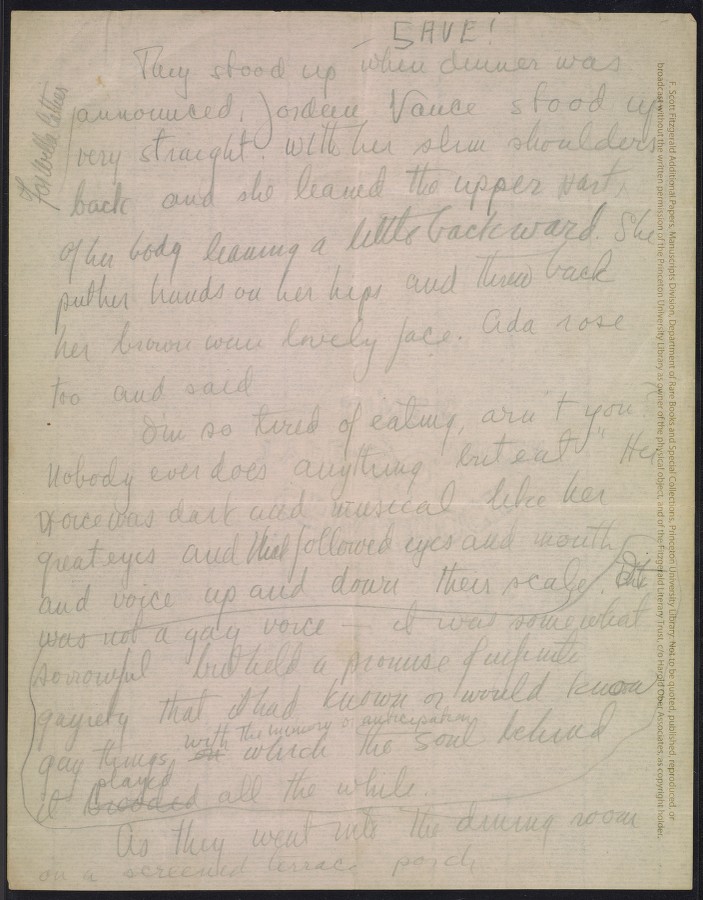

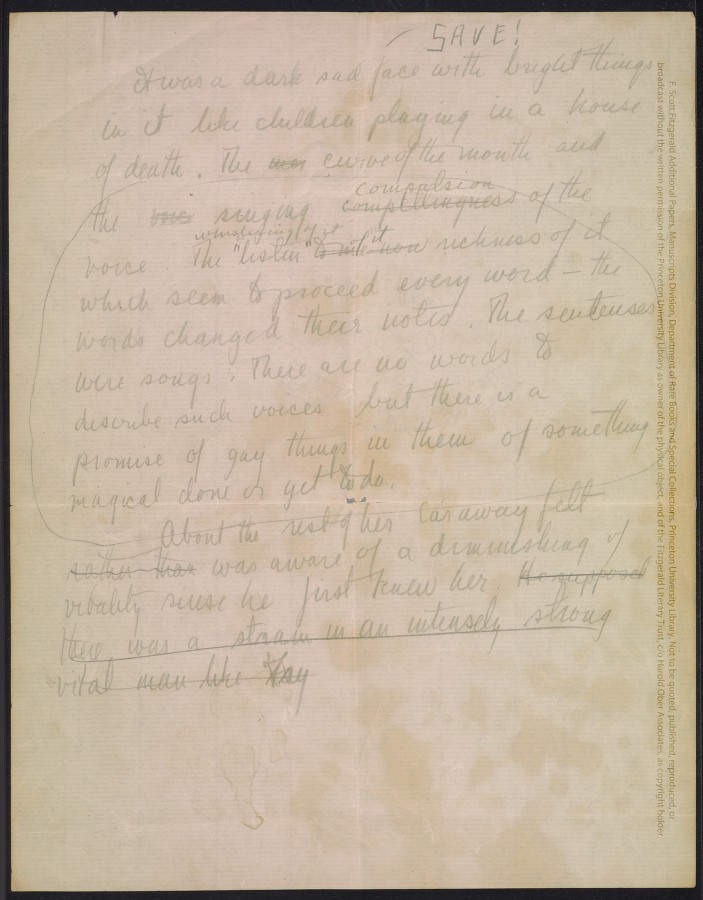

There are only 2 pages remaining from what is thought to be the very first draft of Gatsby– pages he sent to Willa Cather and now referred to as the Ur-Gatsby. In the first draft, Daisy Buchanan was called Ada and Nick was called Dudley, Dud for short.

Good revision, Mr. Fitzgerald.

I love these pages so much– a creator in the act of creating, a moment frozen in time.

He sent these to Willa Cather because he feared the description of Ada was too similar to one of hers. He was asking for her blessing and she gave it.

Two circled passages marked “SAVE” were revised as one for the final version of Gatsby:

“I looked back at my cousin, who began to ask me questions in her low, thrilling voice. It was the kind of voice that the ear follows up and down, as if each speech is an arrangement of notes that will never be played again. Her face was sad and lovely with bright things in it, bright eyes and a bright passionate mouth, but there was an excitement in her voice that men who had cared for her found difficult to forget: a singing compulsion, a whispered ‘Listen,’ a promise that she had done gay, exciting things just a while since and that there were gay, exciting things hovering in the next hour.” (Ch 1)

Fitzgerald agonized over words and his horrible spelling. Fitzgerald heavily revised the galleys in late 1924 and early 1925. He sent revisions to his publisher until the last possible moment, and even later, asking for (yet another) title change after the book had gone to press. Gatsby was published in 1925.

When I first looked at the pages that Fitzgerald sent to Cather, I was astonished to see that the earliest version of Gatsby was written in third person. The final is written from the first person POV of Nick, Fitzgerald’s unreliable and morally confused and besotted narrator. I’d studied Gatsby; I’d taught it. Nowhere else had I read about this sweeping change that Fitzgerald made that gave us Nick’s first person narration, the essence of the novel. And I’m so curious about what prompted Fitzgerald to make such a major change. How did his vision change from those earliest pages to the final? Was it a spark or a deliberation? What I do know, is that it was brilliant, because it’s impossible to imagine the novel written from any other POV.

There is an art to writing, but also craft. Honing that craft to its sharpest point is perhaps the ultimate test for the writer. The soul-crunching work of a career, of a lifetime. The proof that hints at greatness.

Fitzgerald died at the age of 44 believing himself a failure and a hack. But to glance into his revisions is to step into a mystery, to witness grace and alchemy, a writer’s obsession for language and story. And it is inspiriting.

The work endures.

Leave a Reply