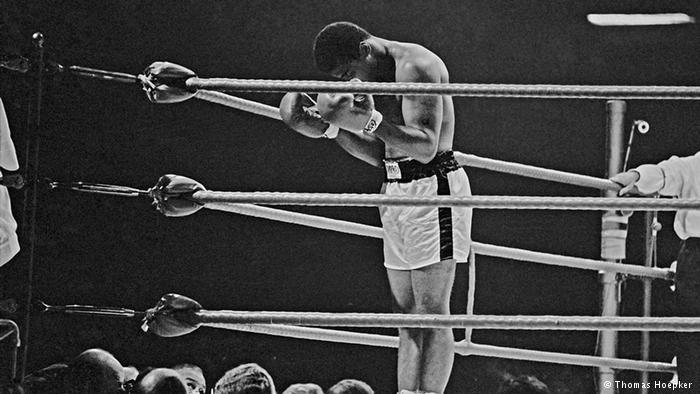

I’m not a fan of boxing.

Watching two humans in hand-to-hand combat, faces bloodied, noses broken. It’s just not for me.

But for a kid growing up in the 70s, Muhammad Ali loomed large. For a Muslim kid, for a brown kid living in a small town in the Midwest, he was legend and myth and superhero.

My earliest memories of Ali are amongst my earliest memories. In 1975, I was four-years old and Muhammad Ali converted to Sunni Islam. The most famous human being on the planet was Muslim. I remember the hype and my parents and their friends gathering around the old box television, bunny-eared antennae at the ready for Ali against Frazier, Norton, Spinks, and the final bruising battle against Holmes. They cheered for the victories and flinched with the blows that fell on the fading Champ. I’m not sure how one man could carry so much on his shoulders, but he was The Greatest. He could carry the world.

Today we talk a lot about representation about the critical importance of mirrors in literature–where children can see themselves. When I was a kid, I eagerly watched Romper Room and waited, oh so patiently, for the end of every episode where the host would hold up the magic mirror and name all the children she could see out there in Televisionland: I can see Tommy and Becky and Johnny and Kathleen and Joe and Bobby and Jennifer.

She never saw me.

Ali was black. He was a man. He was an athlete. I was none of those things. But he was also, almost miraculously, a Muslim, like me. He was a brother to every Muslim on the planet. For that kid, growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, he was the magic mirror. No, he didn’t look like me, but his name was like my name. For me, that was enough. For me, that was everything.

I grew up as Ali battled Parkinson’s, as his brilliant wit and verbal sparring slowed, as he lost the spring in his step, but never the spark in his eye. With the rest of the world, I wept during the torch lighting at the Atlanta Olympics and during half-time at the men’s gold-medal basketball game when Ali received a replacement for the gold medal he’d won at the 1960 Rome Olympics. When a sly smile appeared across his face and he raised the gold medal to his lips with trembling fingers, you wanted to change the world for him. Find a cure, let him speak his poetry again.

A month later, I met him.

The Democratic Convention came to Chicago in August 1996 and through some luck, I be-friended an aide to then Congressman Jesse Jackson, Jr. and wound up in the Jackson family box a the United Center on the night when Bill Clinton was accepting the nomination.

Delegates swarmed the floor, cheers rose to the rafters, people kept referencing the Macarena, Ted Kennedy spoke. Jessye Norman sang with a voice surely heard in the amongst the stars.

Then as if in slow motion, the thousands of delegates crowding the floor, the thousands more in their box seats, turn, like a single body, to the Clinton box and chant, in one tremendous voice: Ali, Ali, Ali.

Muhammad Ali was in the Clinton box.

And because this happened in an age before camera phones and instant documentation, some of the moments blur into the edges of my memory.

But this moment is burned in my brain:

After Clinton accepts the nomination and the balloons fall and the confetti wafts down, the scene swirls around me and I move in a patriotic daze, jubilation thick in the air. As I exit the box and walk toward the escalator, I see a small group of very tall men gathered in a semicircle, at the center is Muhammad Ali. I squirm my way in between the members of the entourage.

Mouth agape, heart thudding in my ears. I am 5 feet away from Muhammad Ali.

His eyes scan the crowd and then he stares at me.

Muhammad Ali looks at me. He raises his right hand to point a shaky finger in my direction. His eyes widen, bursting with surprise and humor. In those eyes, I see the Ali I remember from my childhood.

I am not exactly sure what is happening because it is impossible that The Greatest is looking at me and then one of his entourage says, “He’s calling you out” and an invisible hand nudges me forward.

I stand before Muhammad Ali and manage to squeak out an, “As-salāmu ʿalaykum.” He shakes my hand; envelopes it with both of his– enormous, gentle. I look in his eyes, they are bright and fierce and he bends all the way down to my ear– a giant leaning over, his head leaving the heavens to whisper in my ear, “Waʿalaykumu s-salām. Where are you from?”

As I utter that my family is from India, two men motion him away. He looks at me once more and in an instant is gone.

Floats like a butterfly.

Childhood heroes occupy a diaphanous space in our imaginations where they exist, beyond time, un-flawed, on a pedestal. Sometimes they are best left there–the green light at the end of a dock, untouchable, immortal, unreal.

But Ali was a man who walked amongst his fellow human beings. He wasn’t the greatest because he defied his mortality, he was great because he embraced it.

Ali loved his blackness, revered his Islam, grappled with his mistakes, stood up, spoke his truth, flouted his haters, fell from the heights and rose up, higher. And higher, still.

Black. Muslim. American. Legend.

Rest in Peace.

Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raji’un

Beautiful! Thanks for sharing this touching story. ❤️

Thanks for reading! xoxo

Loved it. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks, Brian. I had meant to write this up years ago, alas, the time presented itself.

The more I read about this man, the more I respect and admire him. Thanks for sharing such a beautiful moment.